Patellar tendinopathy is a common source of anterior knee pain which is characterised by pain localised to the inferior pole of the patella when under load.

There are a number of risk factors for developing patellar tendonopathy but an exact and specific cause in unknown. Until fairly recently the condition was known as patella tendonitis hinting at an acute inflammatory cause. However through histological studies we know this to be untrue as the key feature of the condition is degenerative changes of the tendon rather than the presence of inflammatory cells. Therefore the condition has been renamed tondinopathy to reflect the degenerative and chronic cause of the conditon.

As there is minimal acute inflammatory involvement in the condition anti-inflammatory medication is not effective as there is no acute inflammatory process to disrupt.

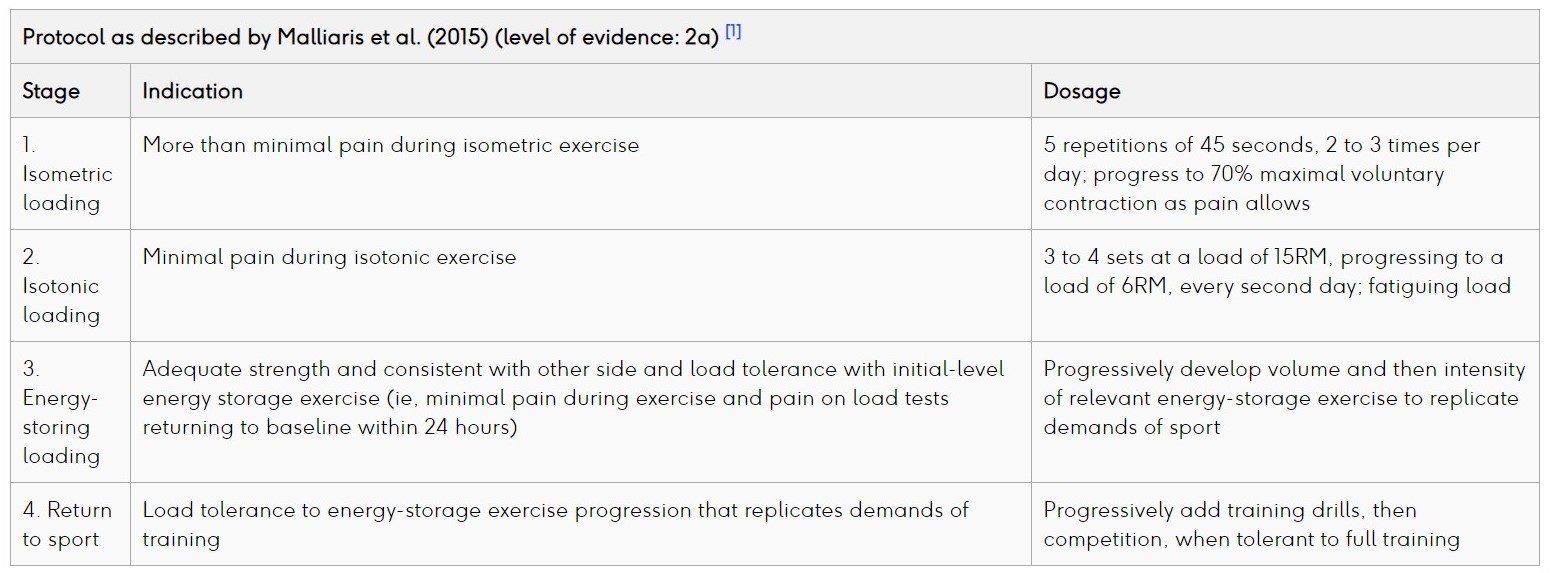

The most widely accepted treatment for patellar tendinopathy is eccentric exercise therapy (EET) after a short period of rest. Programmes such as Malliaris et al (2015) are commonly used within clinical practice and recommended by NICE however these exercises can be pain provoking and irritable. There is also some debate about their effectiveness for allowing early return to activity.

For a number of years there has been growing evidence for an altervative and less pain provoking treatment than eccentric loading; progressive tendon loading exercises within limits of pain (PTLE). Although there is growing anecdotal and logical support from switching from EET to PTLE there is limited evidence which compares the effectiveness of the two approaches. The new JUMPER study aimed to compare PTLE and EET based on clinical outcome after 24 weeks in patients with patellar tendinopathy.

Deep Dive into Tendons with Ebonie Rio

Methods

The JUMPER study was a stratified, single blinded RCT that included athletes from all levels. Inclusion criteria:

- Age 18-35

- History of knee pain local to the patella induced by training / competition

- Participate in sport minimum of 3x/wk

- Structural tendon changes shown on USS / Doppler

- VISA-P score of <80 / 100

Participants were excluded if: injury was acute, prior knee surgery had taken place without full rehab, known inflammatory disease, daily use of drugs or recent injection which effect the tendon, high levels of cholesterol, previous tendon rupture, inability to perform the exercise programme, participation in another trial / treatment programme or signs of other knee pathology. For details of the clinical examination and randomisation head to the article which is available for free and open access and refereced at the bottom of the text.

The primary outcome was VISA-P questionnaire which was admistered at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks. Secondary outcomes were return to sport, exercise adherence and patient satisfaction. In total 76 participants were randomised into the trail with 67 making it to the end of the 24 weeks.

Intervention

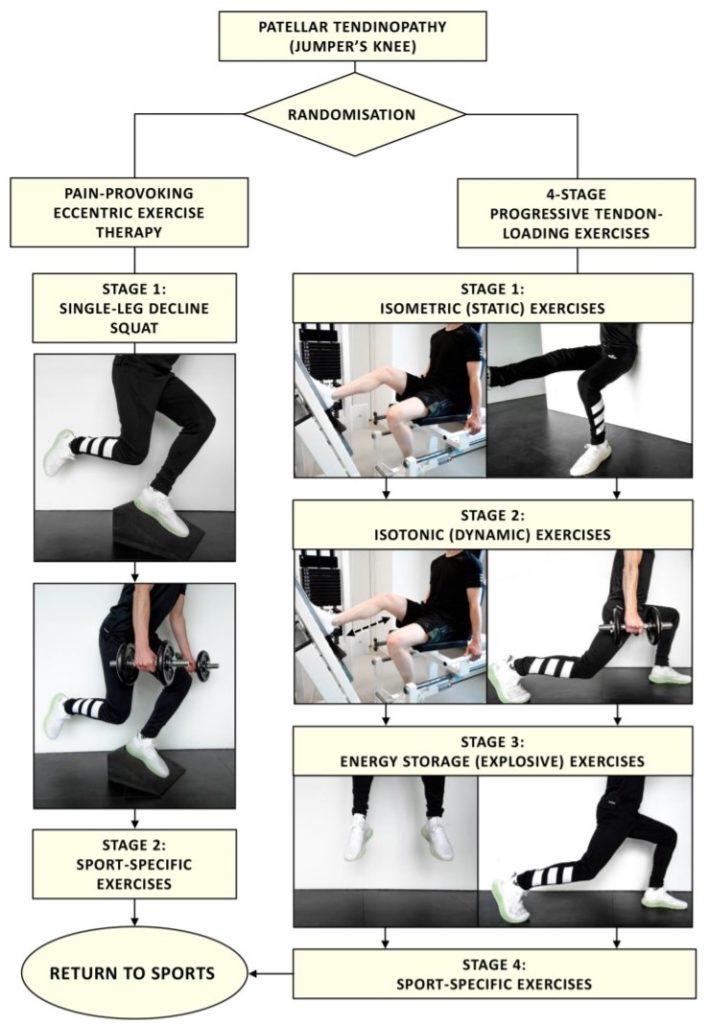

Patients were randomly assigned to PTLE within limits of acceptable pain (intervention) or pain-provoking EET (control) for 24 weeks. Exercise plans and videos were available for all patients via the trial website (currently inactive) and via educational leaflets (currently unable to access).

Patients in the intervention group performed daily static isotonic, explosive and sport-specific exercises consecutively within the limits of pain. Progressive load was adjusted according to individual response (use VAS).

The PTLE programme consisted of 4 stages:

Stage 1: daily isometric exercises (single-leg leg press / leg extensions) 5x45s mid range quads isometric hold at 70% MVC.

Stage 2: stage 1 exercises on first day and new isotonic exercises on the second day. These exercises were also performed as a single-leg leg-press or

leg-extension, and started with 4×15 repetitions between

10° and 60° of knee flexion and slowly progressed to 4×6

reps with increasing load and knee angles between almost

full extension and 90° flexion.

Stage 3: plyometric loading and running exercises (jump squats, box

jumps and cutting manoeuvers) on every third day, starting with

3 sets of 10 repetitions using both legs and slowly progressed

to 6 sets of 10 repetitions using one leg. Isometric and isotonic

exercises were continued on every first and second day, respectively.

Stage 4: sport-specific exercises, which were characteristic for the type of sport. Patients were instructed to gradually return to sport-specific training, performed every 2–3 days to allow for recovery from high tendon-loading exercises. In this stage, the isometric exercises of stage 1 were continued on days that the sport-specific exercises were not performed.

Progression to each subsequent stage was defined using individualised progression criteria, based on the level of pain experienced during a pain provocation test that consisted of one single-leg squat. If the VAS-score was 3 or less and exercises of the stage were performed for at least 1 week, progression to the next stage was advised. When all the exercises in stage 4 were performed within the limits of acceptable pain (VAS score ≤3 points), return to competition was recommended.

Once returning to sport stage 1 and 2 maintenance exercises were advised twice per week. The fastest possible time to return to sports was after 4 weeks, according to this PTLE programme.

Deep Dive into Tendons with Ebonie Rio

The EET control group performed their exercsies twice daily for 12 weeks. The exercises were performed on a decline board with a 25 degree slope. Stage 1 of the EET consisted of a single-leg decline squat, where the downward component (eccentric phase) was performed with the symptomatic leg and the upward component (concentric phase) mainly performed using the contralateral leg. Patients were instructed to perform the exercises with pain (VAS score ≥5 points on a scale 0–10 during the exercises).

Stage 2 was initiated if there was complete adherence to stage 1 exercises and when there was acceptable pain during eccentric exercises with additional weights (VAS score ≤3 points on a scale 0–10, the amount of weights was not specified).

Stage 2 exercises consisted of sport-specific exercises, which were characteristic for the type of sport. Maintenance exercises consisted of stage 1 exercises twice a week. Patients in the EET group were allowed to return to sports after 4 weeks. We advised to do this if a single-leg squat could be performed within the limits of acceptable pain (VAS score ≤3 points on a scale 0–10). The decline board with a 25° slope was provided for patients allocated to EET

Clinical Implications & Results

In this RCT involving 67 patients progressive tendon loading exercises were more effective than eccentric loading exercises in terms of patient satisfaction, VISA-P score and returning to sport at pre-injury level within 24 weeks.

It’s important we don’t get ahead of ourselves and start radically changing our clinical practice at this stage as this is an RCT of 67 people. For some patients PTLE may be a more suitable option than EET particularly if they are not adherent to eccentric exercises or if they find it too irritable and therefore nunable to adhere to the programme.

It is worth considering that the participants were or mixed sporting ability and performance and therefore it is not possible to draw firm conclusions about whether or not this influences the effectiveness of either PTLE or EET. Results could be more specific to either population if the study was designed differently.

Additionally the exercise was unsupervised and was performed in a patient population who are familar with technical exercise. Results are likely to be different in a population who are not familar with this level of technical exercise and to counter this supervised exercise may be required, at least for the initial stages of the exercise programme.

Another caveat is that if the worst case scenario of the sensitivity analysis of missing data is correct then the better clinical outcome of the PTLE group no longer holds true. However this worst case scenario is unlikely.