Akbar Kare is a therapy centre offering free services to children with developmental disabilities in Pakistan. Yvonne Frizzell is a Physiotherapist who has kindly written about her experience working in Pakistan. She was a facilitator during the Cerebral Palsy MOOC which ran in 2016. Please take the time to read this voices post it is emotional and thought provoking.

I first arrived in Peshawar in 1984, leaving my work as a paediatric physiotherapist in London in a progressive, well-funded, inner city, community paediatric service. I have spend 32 years between Pakistan and Europe learning to adapt, and re-adapt, to both cultures, bridging the knowledge and experience gap between the two. I realised that this was not going to be a one way process; both cultures have much to offer each other. Originally I volunteered for 5 years in a local school and therapy centre in Peshawar,i only returning to Europe for my own children’s education in 1990. As our children left for University my husband and I decided on another change of life plan. It eventually led us back to Peshawar and 11 years ago we started Akbar Kare therapy centre in Peshawar.

This summer, 2016, I was asked to participate as a facilitator for the ‘Managing Children with Cerebral Palsy’ course developed by ICRC and Physiopedia. I wondered what I could add to the wealth of knowledge and practise that exists in the developed, highly academic regions of the world. I am very grateful that I accepted the challenge.

Disability in the majority of the world’s population is a largely neglected area and rights and facilities are provided by charities and governments haphazardly and irregularly. The recent UN Sustainable Development Goals that were inaugurated in Sept 2015 in Washington show that of the 17 goals 11 impact on children with disabilities.

Worldwide disability affects roughly 650 million people. According to the UN Development Program (UNDP) 80% per cent of persons with disabilities live in developing countries. Pakistan has an estimated population of 200 million. Approximately 33% of the population is under 14 years of age and 23 % of the population live below the poverty line.

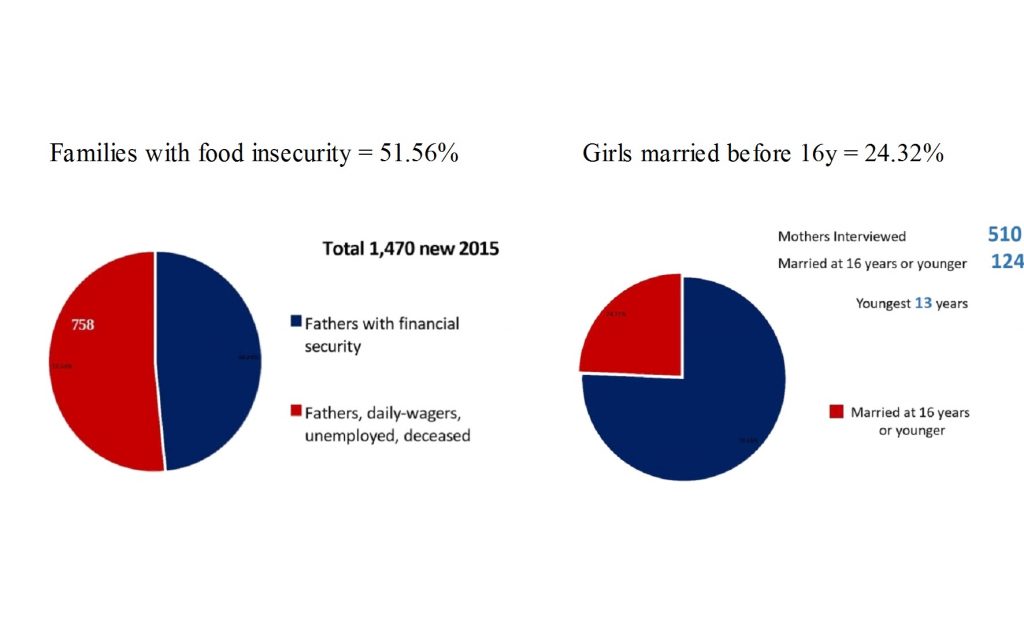

It is not difficult to imagine that childhood disability is a major issue in Pakistan. Poverty and lack of educational or other social care resources are absent for most of these families. The work required of our clinic is immense and we operate under other constraints and considerations.

Complicating these stark statistics, based in Peshawar the Provincial capital of K.P., we work in a region that is described as ‘in-conflict’ and has been an area which for many years has seen refugees from Afghanistan and Internally Displaced People (IDP’s) settle and raise families. The burden on basic resources and the Health infrastructure has been heavy. Acute health problems and emergency services in government hospitals have been overwhelmed. In this climate of stress children with disabilities have little or no access to rehabilitation or education. Endemic poverty commonly exacerbates the problems families face.

These issues will not get any better soon.

“(There is) projected increases in the number of disabled children over the next 30 years, particularly in the developing countries, due to malnutrition, diseases, child labour and other causes.”

In January of 2006 what did we hope to achieve as we opened our first centre for free therapy to children with developmental disabilities? I echo what has been said by others: ‘if knew then what I know now I might have been too daunted to even begin.’

In Pakistan Disability rights are not implemented, childhood is not supported by society. Our children do not go to school unless they live in close proximity to a district facility and only then if their impairment is not so involved, if it allows them to have reasonable ability to communicate and be self-sufficient in toileting and feeding. Teachers for children with special needs are certainly rare.

Any visiting overseas trainers need to be aware that these families work in isolation, no school, no government service, no benefits, no counselling, no respite, and no social welfare safety net.

This year at the introduction to the Managing children with Cerebral Palsy course Barbara Rauvii ; said one of the aims of the course was to bridge the gap of knowledge and experience between the developed and underdeveloped communities working with children with Cerebral Palsy.

My experience in developing a service for children in this deprived community gave me my reason for choosing to help with this course. I learnt that the issues I see in Pakistan are reflected in the experiences others from around the world face. Providing good rehab experiences in under resourced areas is difficult. Physiotherapy in K.P. as a profession, as in many developing countries, is in its infancy. We have limited availability of OTs or SLTs, and none with paediatric experience. Considering treating children separate to adults had not been widely acknowledged as necessary in the 1990’s, or on my return in 2006. It is still not recognised in Government hospitals. I was unprepared for the resistance at first to ‘getting down and playing with children’ by our physiotherapists. White coats and desks were very popular! A culture exists of Physiotherapists as DPTs, doctors of physiotherapy. Many children mainly crying in therapy sessions is treated as acceptable.

Akbar Kare 2016

In our centre we cannot be limited exclusively to physiotherapy for motor development. Children with disabilities may have many areas of development that needs attention to enable them to participate with their families and in their communities. Most have no government facilities available to them, they are on their own entirely. Only 6.4% of our children attend school. Families live with poverty that is made exacerbated by the cost of visiting doctors, paying for consultations and prescriptions, and looking for cures.

Many girls are married before they reach 16 years and are often unprepared and malnourished. Planning an intervention that accommodates the family’s life style and abilities to promote a better quality of life for the child is sometimes more difficult than expected. Many families live jointly with grown-up sons marrying and bringing the wife into his home and so there may be several families living together. All with a grandmother who is respected and expects to be involved in her daughterin-laws decisions on bringing up her children. Often this is positive as there is support both financially and physically from others adults in the home. But sometimes a child with disabilities is seen as being a burden that should not be given quite so much attention.

Planning an intervention that accommodates the family’s life style and abilities to promote a better quality of life for the child is sometimes more difficult than expected. Many families live jointly with grown-up sons marrying and bringing the wife into his home and so there may be several families living together. All with a grandmother who is respected and expects to be involved in her daughterin-laws decisions on bringing up her children. Often this is positive as there is support both financially and physically from others adults in the home. But sometimes a child with disabilities is seen as being a burden that should not be given quite so much attention.

Or there is blame and superstition associated with disability. Mother of a girl with Athetoid CP:

“..my sisters-in-law would not come near me or let their children play with my daughter, they thought they may have a child with disabilities if they did’

We have to be imaginative in delivering a service that will improve the quality of the child’s life. This demands a lot of young newly graduated therapists. The challenges lead to good teamwork among the staff and a sense of achievement when they see progress. The first three months for any new employee at AKi is an intensive in-service training period. Then they are assigned supervisors to guide them in their first year. Case discussions and study days are regular.

We have 7,850 children registered, and in the past three years that has been increasing by more than 1,500 each year. We employ ten Physiotherapists and three assistants and have a well quipped workshop to make our own postural aids. We have three appliance officers in the workshop. We have one special teacher and her assistant.

A variety of staff are needed for running a centre that offers a variety o f services. We can offer meals to families who have travelled long distances to attend. Not many rehabilitation centres here have facilities to do this, but it is essential to allow families relax and gain as much benefit as they can, especially if they cannot come again for months. We need good security arrangements for the centre as Pakistan has seen attacks on schools and community polio vaccinators.

f services. We can offer meals to families who have travelled long distances to attend. Not many rehabilitation centres here have facilities to do this, but it is essential to allow families relax and gain as much benefit as they can, especially if they cannot come again for months. We need good security arrangements for the centre as Pakistan has seen attacks on schools and community polio vaccinators.

All the staff follow the commitment of the centre in empowering families as active team members. Listening to and involving care givers is essential to plan how we will make changes that fit in with the family’s life style and allow participation of their child, if we want to make a real difference.

Essential to the service is continuous professional development. E-learning is proving a powerful tool, providing access to quality training materials to use in our study days, practical workshops and for reference. This has become available to us over the past decade and we have fully embraced it. One consequence of the confidence gained in using technology is that we are now almost a paper free centre with a software system to record and monitor all areas. This gives us access to powerful statistics for advocacy and a continuity of care for children.

At the other end of the technology spectrum we make aids that are simple, appropriate to local needs, and are recyclable. As they wear out, or are outgrown, they can be used as fuel for cooking and heating the family home. The child’s need for the next appliance is then reassessed and supplied. Our aids are cheap and simple to make, but robust. They are custom made to each child’s needs.

We have a selection of postural adaptations for chairs, wheelchairs, standing frames and prone boards made in-house. All aids supplied are made in our workshop or from local sources. The clinicians and technicians work closely together to get best result.

We use POP and fibreglass for serial splinting. This is a developing service to help manage equinus. We have access to orthotics through ICRC. We do serial casting, and AFO’s are prescribed by us as needed. Botox is unaffordable for our families or for the centre to fund.

We have a feeding program for children with difficulties in oromotor and recurring respiratory illness, often due to aspiration. We show good positioning and how to help a children develop more functional and safe feeding. We advise on local affordable ingredients for improving quality and type of food suitable for helping young children thrive. Often the siblings are also malnourished and all the family benefit from the support we can give. We show how to clean teeth, first by massage with fingers until a child can tolerate a toothbrush.

Accepting we need to work in a variety of areas at our centre enables us to adapt to family life and the child’s needs within their family. The family must become the primary executive of the management of the child’s progress so we make the most of their time at the centre. We are the resource centre for specific treatments using our professional knowledge but without the family we will not be effective.

We hold a monthly party for childre n and their families and a hand washing day. These days are a means to bring families together for social occasions and not for anything related to their child’s disability. Rehabilitation works if the child has a place in a community that is seen to be their right.

n and their families and a hand washing day. These days are a means to bring families together for social occasions and not for anything related to their child’s disability. Rehabilitation works if the child has a place in a community that is seen to be their right.

We have one Teacher with special needs experience. She is developing simple communication aids for children to use when they meet people. These are: ‘Who am I?’ laminated cards. This program will be expanded in 2017 to use more augmentative basic communication aids. Children with disabilities that affect their ability to speak are often ignored and the people talk about them, but not to them. These cards show that the child has her own thoughts. Our teacher also takes classes to help children prepare for school placements that we must advocate for with local schools

AKi into the future; what will we become?

It has taken us eleven years to build skills, slowly discovering how we can be effective in improving the lives of children and their families. This has to be thought of as a continuum. We are a ‘work in progress’.

- We are developing an outreach program based on the Manual, ‘Getting to Know Cerebral Palsy’. We have translated the manual into Urdu and have begun a pilot project this December 2016 in Swat district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A local Health visitor has been recruited to help us. If families can be helped locally then the burden of travel and of losing a day’s pay when the father is a day labourer, is avoided.

- We have prepared a short training course for Medicine Sans Frontiers (MSF) nurses in handling and care of premature babies in the New Born Baby Unit. This will be an introduction to positioning, feeding, safe swaddling and recognising atypical development and red flags for developmental issue. This will be begin in January 2017. We have been giving this course informally but have been asked to document our work with them so that it can be part of an ongoing training package. We take referrals from MSF as they discharge babies to make sure they do not lose contact. We offer monitoring of their neurological development at 2mths, 4 mths and 6mths, or as required.

- We have an awareness program for junior government paediatricians and newly qualified PTs about the importance of Early Intervention.

- We have been offered a fully equipped workshop for making selected orthotics with training from ICRC. This will enable us to become independent in assessing and supplying well-fitting functional AFOs. This is part of our development for 2017.

- We are working to have a purpose built centre on its own land to support a network of outreach programs in the Province. Ideally we hope we can become a resource centre with expertise that can offer training to people working in the community to help children with disabilities have a better quality of life.

Akbar Kare is indeed a work in progress but we encourage others in developing and under resourced regions to believe it is possible, with limited funding, to look at a child with disability and the family holistically in one centre.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals look to promote the global health and development of people and Nations. If we do not address the needs of children and children with disabilities we are negatively influencing the whole of our societies. Parents and siblings cannot thrive when one or more children in the family is denied a good life.

Many thanks to Yvonne. If you wish to contact her about her time in Pakistan you can here. If you would like to write a voices piece then please get in touch.