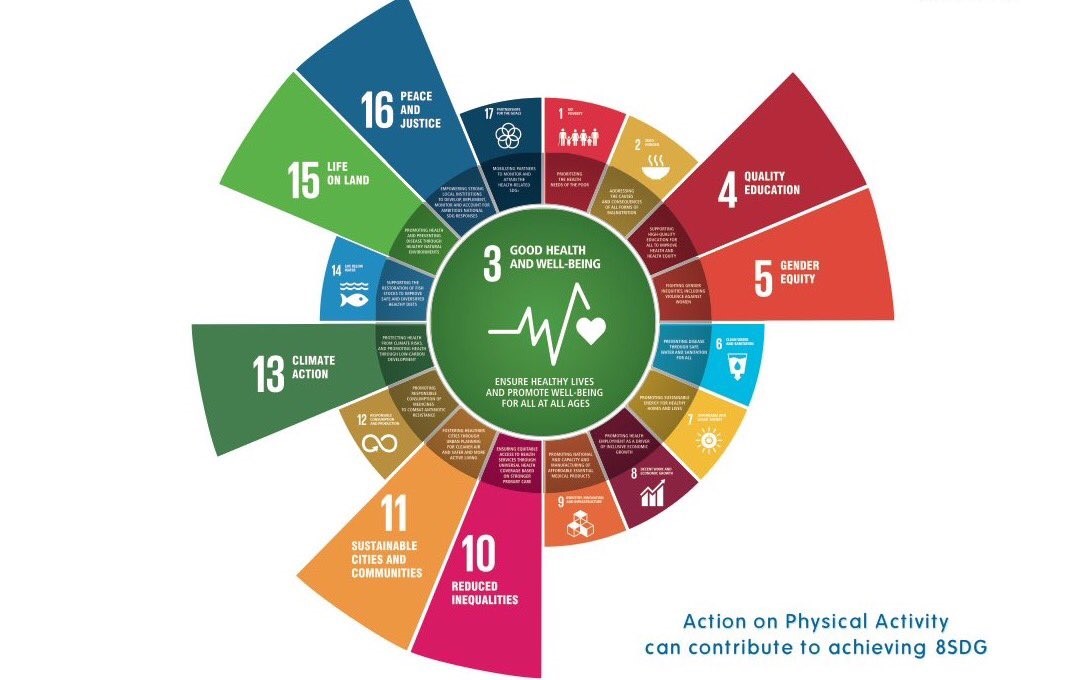

Exercise is good for everybody! If we all performed the recommended amount of physical activity or exercise on a weekly basis, this would likely be the end of the story, and I could stop writing this blog. But the reality of exercise is that most of us don’t do as much as we could or should, for a number of different reasons. We may know that exercise can help anybody get fitter, loose weight, prevent or manage illnesses, and make us feel happier. Interestingly physical activity and exercise can address 8 of the World Health Organisations Sustainable Development Goals (image 1) leading to improvements in population health and well-being. But what do we know about the “research” and the “reality” of exercise for people living with HIV? The answer is quite a lot.

The terms “physical activity” and “exercise” are often used interchangeably. However there are important distinctions between the two for both research purposes, and the reality of helping every person move more. “Physical activity” is defined as any movement, carried out by our muscles that requires energy – therefore pretty much any movement we do is physical activity. Whereas “exercise” is defined as planned, structured, repetitive and intentional movements, with the intention to improve or maintain physical fitness.

Robust evidence on the safety and effectiveness of exercise among people living with HIV, has been published in many Cochrane reviews for both aerobic and progressive resistance exercise; 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2010, 2016 and 2017. In summary performing either aerobic (eg: cardio exercises like cycling or swimming) or a combination of aerobic and resistive exercise (eg: strengthening exercises) is safe and effective for people living with HIV who are medically stable, when performed 3 times per week for at least 5-6 weeks. This can result in improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, strength, body composition, weight and quality of life.

However new evidence suggests that people living with HIV are insufficiently physically active in comparison to other health populations and present as the most sedentary population within the existing literature. As physical activity and exercise can improve the fitness of the heart and lungs (cardiorespiratory fitness), which can moderate the risk of cardiovascular disease (eg: heart attacks), it is worrying that people living with HIV have the lowest cardiorespiratory fitness levels in comparison to other vulnerable populations. Additionally the rate of dropout from physical activity interventions is also highest amongst people living with HIV. Consequently it has been proposed that specialists in exercise and health, such as Physiotherapists, should be included into the multi-disciplinary team supporting people living with HIV.

Research from Canada has identified that the readiness to engage in physical activity among people living with HIV and multi-morbidity (eg: 2 or more additional health conditions) is a dynamic and fluctuating construct, and may be influenced by the episodic nature of HIV and additional health challenges. In addition other factors that can effect readiness include; perceptions and beliefs, social supports, previous experience with exercise and accessibility. Separately in the UK characteristics that affect adherence to exercise programmes include physical, functional and emotional well-being. It is hypothesised that the way people think about the goals of their treatments explains exercise behaviours over and above the effects of the behaviour-specific thinking, and adherence to exercise is stronger among those with more favourable views about the goal.

So what can we do to change this situation then? I think the 1st step is that globally we need to recognise that people living with HIV are at risk of not performing enough physical activity. Unfortunately this is also a repeated pattern for many populations of people living with long-term health conditions. But among HIV services, we need to have a greater understanding that every contact counts and exercise should be discussed in all healthcare settings, including sexual health and HIV services. Incorporating specialists into HIV services eg: Physiotherapists, can also help support people who experience barriers to engaging in physical activity and exercise. Services already exist in the UK that are attempting to address these issues, such as the YMCA positive health programme and HIV Physiotherapy services at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, Mildmay and St Thomas’ Hospital. However they are not universal or accessible to all. Consequently we need to make this a topic for everybody to address. Clinicians need to feel empowered to discuss exercise in all settings; people living with HIV need to be empowered to ask for support when needed in any setting; policy makers need to consider the economic benefits of a more active population; and researchers need to keep up all the hard work on finding out the issues, identifying ways we can help people living with HIV move more for better heath and well-being.

There are things that can be done now. Public Health England provides a range of resources including apps such as Active10 to support engagement in brisk walking, and the couch to 5k app to get people running in just 9 weeks. The NHS also has lots more support to get active and other HIV-specific self-management apps (BeYou+) can support behavioural change. There are campaigns like the This Girl Can, which can be shared and discussed openly. You can utilise the social media champions such as @exerciseworks. There are free online courses about physical activity in the treatment of long-term conditions, and the UK Government provides even more resources. There is a lot more work that needs to be done to ensure that people living with HIV are physically active enough for the benefit of health and well-being. But hopefully this blog has highlighted there is not only a need, but we can make a change now and plan for the future.

Exercise works for people living with HIV. So what are you going to do to make a change?