Whenever I discuss HIV, disability and rehabilitation, I find the topic of disability can generate strong reactions from people. When you read “HIV and Disability”, what thoughts run through your head? Are you angry; because of course HIV is not a disability. Are you confused; because why would HIV be related to disablement? Or are you not thinking anything; because you have never thought about this topic before. None of these responses are wrong or right. But before I continue, I want you to register what you are thinking now, and reflect back on these thoughts later.

In my last blog I discussed how conditions arising from HIV, adverse effects of long-term Antiretroviral Therapy and ageing are resulting in increasingly more prevalent multi-morbidity; which can create physical, cognitive and social health challenges that can be conceptualised as disability. We know that HIV is considered a chronic and episodic condition, with people living significantly longer to near-normal life expectancies, however many people living with HIV may face new or worsening experiences of disability in both high income and low & middle income countries. But to explore this further we need to understand what “disability” means. The term disability can mean different things to different groups of people, some of which are more politically charged than others and some of which have more positive or negative connotations.

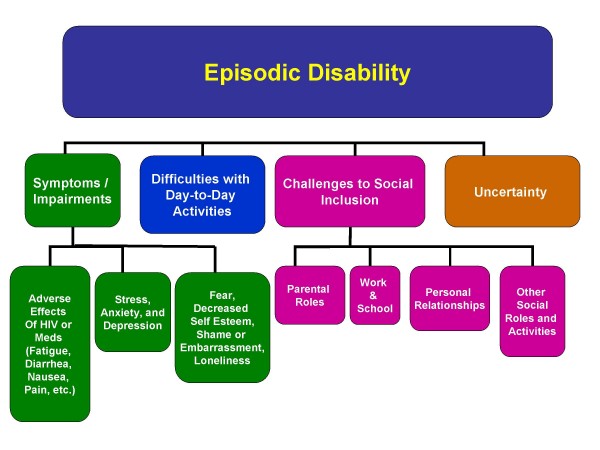

Fortunately the World Health Organisation (WHO) provides a clear definition of disability; as an umbrella term covering impairments (e.g. sensory, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, mental), activity limitations (e.g. mobility, daily activities), and participation restrictions (e.g. work, social life). Therefore for somebody living with HIV, a disability may refer to the disabling effects of HIV, its secondary conditions and the side effects of medications. These disabling effects can be episodic and unpredictable, or permanent. However “disability” may also refer to disability grants or benefits, typically available through local governments, to support people who are unable to work due to long-standing health conditions. Therefore the language around disability is important. It has been argued that historically there has been two separate fields of research;

- People living with HIV and their experiences of disability brought on by the disease and its treatments.

- The experiences of people with disabilities and their vulnerability to and life with HIV.

Interestingly when performing a quick Internet search for “HIV and Disability”, three common themes emerge that I would like to discuss further; Employment rights and disability grants/benefits for people living with HIV; The vulnerability of persons with disabilities to HIV exposure; The disability experienced by people living with HIV.

Employment rights and disability grants/benefits for people living with HIV

In England, Scotland and Wales the Equality Act 2010, provides protection from discrimination in employment, health care and wider society, with the right to request reasonable adjustments. It is against the law to discriminate based on age, sex, religion, race, sexual orientation and disability. You are considered “disabled” under the Equality act if you have a physical or mental impairment that has a “substantial” or “long-term” negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities. HIV is considered a disability under the Equality act, therefore providing people living with HIV protection from discrimination. Therefore legally and politically, the term “disability” could provide positive connotations, even when many people living with HIV may not consider themselves disabled. However in the United Kingdom, a HIV diagnosis does not automatically make people eligible for disability benefits grants, and it’s well recognised that issues around benefits and financial concerns are very real challenges for people living with HIV, and welfare reforms and austerity impact negatively on the welfare of people living with HIV.

As people living with HIV are now living with additional health conditions alongside HIV, ageing and experiencing challenges with participation and independence, guidance on benefits changes and application processes are welcomed, yet also providing alarming data that people may be receiving less support than they previously were entitled too. It is therefore more relevant than ever that the language around disability is understood in the field of HIV, and that we start to utilise the available tools and resources to measure disability to ensure that people living with HIV are not left behind.

Physiotherapists are experts in movement and possess a wealth of experience in measuring disability, providing rehabilitation interventions to address disability, and supporting people living with long-term health conditions to reach their optimal potential. It is in fact a Physiotherapist; Dr Kelly O’Brien, who developed the HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) to measure the presence, severity and episodic nature of HIV. In my clinical practice at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust I lead the outpatient HIV Physiotherapy service, where I have seen an increase in the number of people presenting with significant uncertainty and distress due to upcoming reviews or changes to their existing benefits. This uncertainty can itself be disabling. Yet by using appropriate measurement tools, such as the HDQ, in combination with other functional performance measures eg: gait speed and 5x sit-stand, I am able to measure and report function and disability. Feedback suggests people are experiencing reduced uncertainty and greater participation in meaningful tasks when their function and disability is measured and reported. But also we have seen some positive outcomes in the benefits review process. So is function and disability being measured within the usual continuum of care for people living with HIV? Are enough Physiotherapists supporting people living with HIV? Do we know the level of disability experienced by people living with HIV?

In the UK function and disability measurements are not often performed within HIV services, there are very few HIV specialist Physiotherapists and there is limited data on disability experienced by people living with HIV in the UK. This lags behind our colleagues in Canada and South Africa. With 36.7 million people living with HIV globally, the World Health Organisations Rehabilitation 2030 call to action, should be a siren for the field of HIV globally, that HIV and disability needs to be addressed across all levels including education, clinical practice, research, advocacy, commissioning and policy.

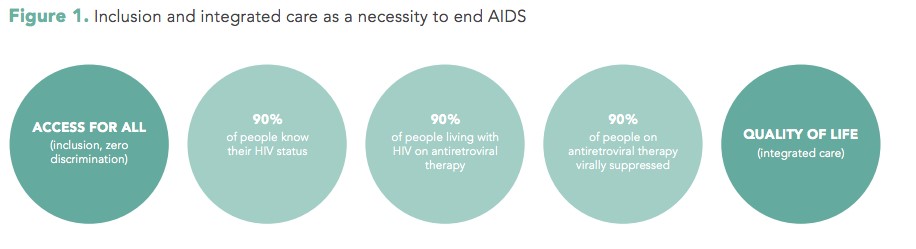

The vulnerability of persons with disabilities to HIV exposure

The United Nations has identified a clear relationship between HIV and disability, which is a cause for concern, because persons with disabilities are often at higher risk of exposure to HIV. The “Disability and HIV Policy Brief” by the World Health Organisation and research from Jill Hanass-Hancock, identifies that people with disabilities may be at higher risk of HIV exposure due to; reduced access to or exclusion from education, information and prevention services due to a lack of disability-specific approaches, which results in people with disabilities having reduced knowledge around HIV and safer sex practices; experience of sexual violence and assault; increased economic vulnerability resulting in transportation or assistive devices becoming unaffordable; services may be physically inaccessible, lack sign language facilities or fail to provide information in alternative formats such as Braille, audio or plain language; and people are more likely to be marginalised due to the double stigma of HIV plus disability. The 2017 UNAIDS report on disability and HIV suggests that people with disabilities have been neglected and excluded in all of the sectors responding to HIV, and highlights disability as a cross cutting issue (see the picture below). The inclusion of disability in the HIV response requires commitment to counteract underlying inequality and discrimination across all sectors, with a shift towards integrating HIV with disability and rehabilitation services. Policies from the World Confederation of Physical Therapy on disabilities and quality services include statements on accessible services, education and equity, therefore Physiotherapists can play a key role within inter-professional teams to address issues experienced by persons with disabilities and HIV.

Disability experienced by people living with HIV

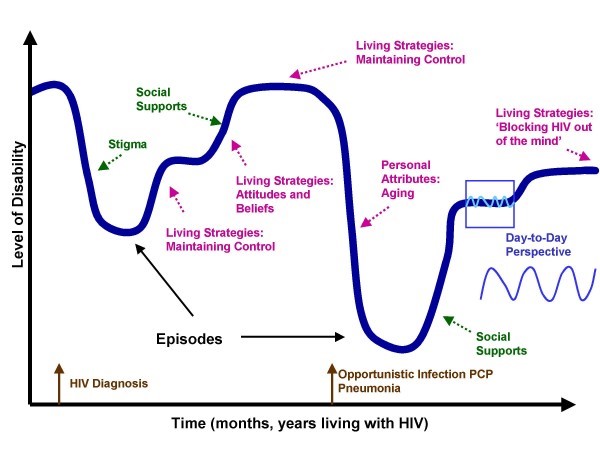

The UNAIDS report on disability and HIV identifies that with increasing chronicity of HIV there are diverse aspects of disability experienced by people living with HIV which impact on quality of life. In Canada the experience of HIV and disability led to the development of the “Episodic Disability Framework” (see the pictures below) from the perspective of people living with HIV, that describes how people living with HIV can experience periods of good health that may be interrupted by health challenges, creating fluctuations or “episodes” of disability. The evidence on the disability experienced by people living and ageing with HIV is mounting, with studies suggesting high levels of disability; with >90% of people living with HIV experiencing 1 or more impairments, 80% experience one or more activity limitation and over 90% experience one or participation restriction. In addition the episodic nature of HIV leaves many older people aging with “uncertainty” related to when their next episode of illness would occur and often results in an inability to plan in advance. Consequently rehabilitation such as Physiotherapy is recommended to address these emerging disability related needs of people living with HIV, and a rehabilitation based approach can support “successful ageing” eg: accepting limitations, staying positive, maintaining social supports, taking responsibility, healthy lifestyles and engaging in meaningful activities . The United Nations “Sustainable Development Goal” of good health and well being, provides an opportunity for rehabilitation professionals to deliver an integrated approach to HIV including disability, to ensure that quality of life is optimised internationally. We still have a long way to go before disability inclusive programmes and policies are widespread, however the recent South African national strategic plan 2017-2022 is a fantastic example of progress, with disability and rehabilitation included throughout many of its goals and objectives. The UK BHIVA standards of Care 2013 recognise the role of rehabilitation professionals within the continuum of care, and with these standards currently under review, I hope that a disability inclusive approach is adopted. The worlds of HIV and disability may finally be integrating, and a recent commitment made to include disability into the political declaration on HIV and AIDS is a welcomed tidal change. My hope for the future is that these signs of a potential paradigm shift to an inclusive HIV response, recognising the role of disability and rehabilitation will continue, evolve and become more widespread. I hope that Physiotherapists internationally recognise their vital role across all sectors including education, clinical practice, research, advocacy, commissioning and policy, and that people living with HIV can access rehabilitation services to optimise function, participation and quality of life.

We still have a long way to go before disability inclusive programmes and policies are widespread, however the recent South African national strategic plan 2017-2022 is a fantastic example of progress, with disability and rehabilitation included throughout many of its goals and objectives. The UK BHIVA standards of Care 2013 recognise the role of rehabilitation professionals within the continuum of care, and with these standards currently under review, I hope that a disability inclusive approach is adopted. The worlds of HIV and disability may finally be integrating, and a recent commitment made to include disability into the political declaration on HIV and AIDS is a welcomed tidal change. My hope for the future is that these signs of a potential paradigm shift to an inclusive HIV response, recognising the role of disability and rehabilitation will continue, evolve and become more widespread. I hope that Physiotherapists internationally recognise their vital role across all sectors including education, clinical practice, research, advocacy, commissioning and policy, and that people living with HIV can access rehabilitation services to optimise function, participation and quality of life. So if I have kept your attention for long enough that you are now reading this paragraph, you might remember that at the very beginning of this blog I asked you to reflect on your own thoughts around “HIV and Disability”.What are you thinking now?

So if I have kept your attention for long enough that you are now reading this paragraph, you might remember that at the very beginning of this blog I asked you to reflect on your own thoughts around “HIV and Disability”.What are you thinking now?

Social media is a strong catalyst for change, so please do share your thoughts, and allow this dialogue on HIV and disability to continue.