What is your immediate response to the word: fibromyalgia?

Perhaps there’s a subconscious bias? Leaning for, against, or on the fence, regards this divisive condition.

Throughout my time as a healthcare professional I’ve seen a clear divide in opinions on Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS); both from diagnosed patients and clinicians. Receiving a formal diagnosis can take a long time (Macfarlane et al., 2016) and often sufferers are bounced to and from specialities, as the intricacies of their symptoms don’t quite fit into the linear moulds a healthcare system would possibly find easier to manage.

Despite this, many professionals are working diligently to promote and support the care of these patients, and while there is disagreement surrounding FMS, it appears the tide could be turning as we understand more about this phenomenon.

Is there a stigma attached to this debilitating illness?

This article resurfaces the potential elephant in the room that is the clinical debate surrounding FMS, its connotations, and non-pharmacological management. For a review of pharmacological interventions, the Cochrane Library for Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care have this week compiled a list of their Fibromyalgia related publications as part of the UK’s Fibromyalgia Awareness week 2017.I must also point you in the direction of the brilliantly witty, Paul Ingraham, whose own article on FMS has some very useful resources.

‘I have pain everywhere, all the time’

‘I have good days and bad days; I just have to live with it’

‘It took them ages to figure out what was wrong with me’

I’m sure many clinicians will have heard similar phrases to these. To me, these comments connote fear, frustration and uncertainty, and are the exact reasons why FMS, and other chronic pain conditions, should be discussed more openly. The sheer complexity of pain and the ambiguity around defining associated symptoms, such as fatigue, lead to conditions many, perhaps, find easier to shy away from rather than tackle head on.

What is Fibromyalgia Syndrome?

(Fibro – connective tissue; myo – muscle tissue; algia – pain)

FMS is a complex disorder involving many factors, considered here as one enveloping condition for simplicity. FMS is a condition of unknown aetiology and unclear pathophysiology; diagnosed primarily on the basis of exclusion of other conditions and in the absence of demonstrable pathology, often by criteria set out by the American College of Rheumatology (Wolfe et al., 2010). Diagnosis ought to be made in primary care, unless there is diagnostic uncertainty, however, there are no specific tests aiding diagnosis rather a broad range of indicators (BSR, 2017).

According to the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR), FMS affects 1 in 20 people in the UK. Its presentation is that of chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain involving both sides of the body, above and below the waist. The reported myalgias and arthralgias have often been found to have no evidence of muscle or joint inflammation on physical examination or laboratory testing, leading to questions around the organic nature of the condition.

FMS is often accompanied by fatigue, mood disorders, sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression. Mood changes are common amongst sufferers, with the colloquial term ‘Fibro Fog’ being used to describe cognitive disturbances such as problems with attention. Additionally, patients can also report bilateral paraesthesia in both upper and lower limbs, including numbness, tingling or burning for example. However, without a neurologic disorder present, such as a radiculopathy, a detailed neurologic evaluation is usually unremarkable.

Fibromyalgia is often accompanied by fatigue, mood disorders, sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression.

Other complaints in FMS can include ocular dryness, bladder and bowel abnormalities, palpitations, sexual dysfunction, weight fluctuations, and night pain to name a few. Symptoms are often exacerbated by stress, overloading physical activity, systemic illnesses and trauma.

Links to Rheumatology

Some studies have reported that patients with FMS meet the criteria for other conditions such as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and that there are links to rheumatic disorders, often coexisting. It has been stated that up to 30% of individuals with autoimmune or rheumatic disorders also suffer from co-morbid FMS (Phillips & Clauw, 2013). However, the link may not be the same for axial Spondyloarthritis (axSpA). A recent study by Baraliakos et al. (2017) investigated the classification criteria for axSpA in patients with a diagnosis of either axSpA or FMS. They found that whilst all FMS patients met the 2010 ACR classification for diagnosis of fibromyalgia (Wolfe et al., 2010); only 2% met the axSpA criteria, owing to the conclusion that FMS patients rarely meet axSpa criteria.

Historically, FMS was considered a condition absent of inflammatory processes but this may not be the case. A study by Bäckryd et al. (2017) identified an ‘extensive inflammatory profile’ when assessing systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation in FMS patients. Bäckryd and colleagues (2017) don’t give an explanation for their findings of inflammation but do state that the notion of FMS being psychogenic ‘should be seen as definitively outdated’.

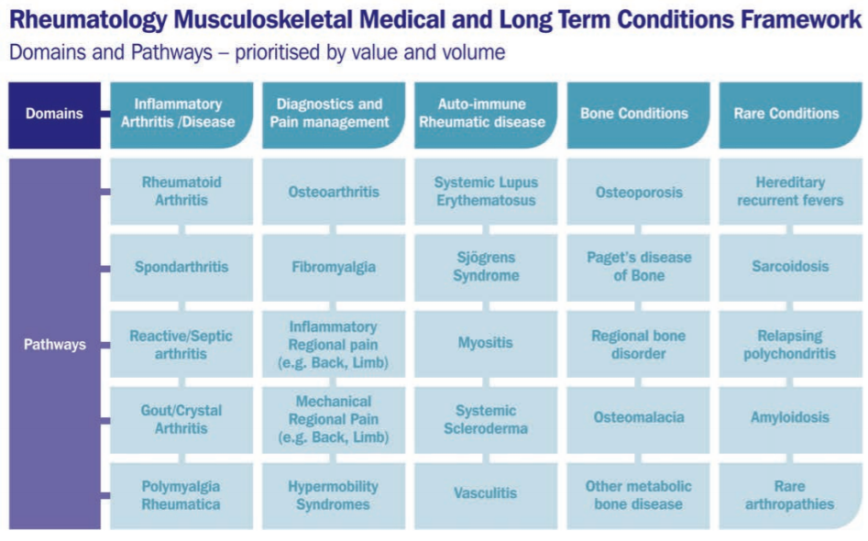

More often than not, FMS patients often fall under the jurisdiction of Rheumatology and the condition is outlined in the BSR’s long term conditions framework under the ‘Diagnostics and Pain Management’ domain (BSR, 2015). However, in BSR’s August Parliamentary Briefing, it states that Rheumatology services should not be utilised for the further management of patients with FMS, unless the patient or primary care clinician is unable to manage the condition. They emphasise that FMS treatment, albeit unclear in itself, be predominantly in primary care.

Clearly the symptoms of FMS are complex and extensive, but the difficulty often lies in the clinical examination; patients may look well with no obvious abnormalities on physical examination other than myofascial tenderness. Radiologic and laboratory studies may well be normal too. Thus, with the other aforementioned unremarkable findings, the clinical debate of FMS is usually surrounding whether it is psychogenic and considered a functional somatic condition or whether it is a complex pain processing dysfunction (BSR, 2017).

Chronic Pain in FMS

FMS doesn’t fit neatly into defined boxes of pain, ‘boxes’ that likely merge anyway; since chronic pain in itself is largely an intriguing enigma. If FMS were purely nociceptive or purely neuropathic, for instance, I’m sure myself and others would find the presentation easier to comprehend clinically. Even when we consider ‘central sensitisation’, we don’t quite capture the complexity of FMS.

There are proposed individualised, physiologic interactions of central and peripheral nervous system signalling which are coupled with familial/genetic factors also (Phillips & Clauw, 2013). Some patients have symptoms of allodynia and hyperalgesia in addition to the above-mentioned paraesthesia without any clear nociceptive or neuropathic lesions. Further still, Phillips & Clauw (2013) discuss alterations in centrally acting neurotransmitters also. The go on to mention a ‘pain prone phenotype’ in people with FMS. Characteristics being: female gender, early life trauma, personal or family history of chronic pain, personal history of other centrally-mediated symptoms (insomnia, fatigue, memory problems, mood disturbances), and cognitions such as catastrophizing.

The clinical debate of FMS is usually surrounding whether it is psychogenic and considered a functional somatic condition or whether it is a complex pain processing dysfunction

FMS is a condition gaining more awareness as research grows however unanswered questions remain. It seems to me that despite the emerging evidence of a complex pain processing in these patients, this may still be overlooked, hence why some still consider there to be a difficult-to-shake stigma. The European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) recognises there are ‘abnormal pain processing and other secondary features’ in FMS (Macfarlane et al., 2016). Their recommendations demand ‘comprehensive assessment of pain, function and psychosocial context’ in order to achieve optimal management. The EULAR recommendations set out principles of approach to management aimed at improving health-related quality of life (HRQL), balancing benefit and risk of treatment, and make clear the need for tailored therapy to the individual and the first-line role of non-pharmacological therapies.

Exercise as Management in FMS

In an age where evidence based practice continues to blossom, there remains a paucity of good quality evidence around Fibromyalgia. In a Cochrane review involving 264 studies (Geneen et al., 2017), people with chronic pain conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia, among others, were examined to ascertain the benefits of physical activity (PA) and exercise. The interventions included; aerobic, strength, flexibility, range of motion, and ‘core’ or balance training programmes, as well as yoga, Pilates, and tai chi. The quality of the available evidence was low but there were some favourable effects (small to moderate) in reduction in pain severity and improved physical function suggesting PA and exercise a viable treatment.

Another Cochrane systematic review (Bidonde et al., 2017) evaluated the effects of aerobic activity specifically in people with FMS. Bidonde and colleagues (2017) could not be certain about the effects of one aerobic intervention against another, nor against controls, as the quality of evidence was low to very low derived from single trials only. Nevertheless, the authors’ conclusions indicated that aerobic exercise probably improves HRQL and suggested that aerobic exercise may slightly decrease pain intensity, may slightly improve physical function, and may lead to little difference in fatigue and stiffness.

Busch et al. (2013) investigated the effects of supervised resistance exercise training in women with FMS, comparing against either no training or aerobic training (progressive walking). With 5 studies in the review and 219 women participants in total, they predictably rated the evidence as low quality but suggested that moderate- and moderate- to high-intensity resistance training improves multidimensional function, pain, tenderness, and muscle strength in women with FMS.

The Elephant in the Room?

Anecdotally, it seems many people with fibromyalgia are passed from pillar to post around healthcare and I often wonder whether the journey, so similar for many, need be so tortuous. FMS, for most, is certainly an incapacitating condition to suffer, and for clinicians, a complex beast to tame. It may coexist with other disorders, such as inflammatory rheumatic diseases and non-inflammatory musculoskeletal pain, whilst swimming in a mix of altered pain processing. Particular attention should be given to identifying the source of symptoms in FMS when making decisions regarding treatment and that it should be holistic and individualised using a multi-disciplinary approach.

Do people have preconceptions? Perhaps. One just hopes we, as clinicians, don’t shy away from FMS.

This week is Fibromyalgia Awareness week, join the conversation.

Chris

References

Bäckryd E, Tanum L, Lind AL, Larsson A, Gordh, T. (2017) Evidence of both systemic and neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia patients, as assessed by a multiplex protein panel applied to cerebrospinal fluid and to plasma. Journal of Pain Research,10, pp.515–525.

Baraliakos, X., Regel, A., Kiltz, U., Menne, H., Dybowski, F., Igelmann, M., Kalthoff, L., Krause, D., Saracbasi-Zender, E., Schmitz-Bortz, E., & Braun, J. (2017) Patients with fibromyalgia rarely fulfil classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis, Journal of Rheumatology.

Bidonde, J., Busch, A.J., Schachter, C.L., Overend, T.J., Kim, S.Y., Góes, S.M., Boden, C. and Foulds, H.J. (2017) Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. The Cochrane Library.

British Society for Rheumatology (2015) The State of Play in UK Rheumatology: Insights into service pressures and solutions. [Accessed 11th May 2017 https://www.rheumatology.org.uk/Portals/0/Policy/Policy%20Report/Rheumatology%20in%20the%20UK%20the%20state%20of%20play.pdf].

BSR (2017) British Society for Rheumatology’s Parliamentary Briefing on Fibromyalgia [accessed September 2017: https://www.rheumatology.org.uk/Portals/0/Policy/Briefings/Fibromyalgia%20Syndrome.pdf]

Busch, A.J., Webber, S.C., Richards, R.S., Bidonde, J., Schachter, C.L., Schafer, L.A., Danyliw, A., Sawant, A., Dal Bello‐Haas, V., Rader, T. and Overend, T.J., (2013). Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia. The Cochrane Library.

Clauw, D (2014) Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA; 311, pp.1547.

Geneen, L.J., Moore, R.A., Clarke, C., Martin, D., Colvin, L.A. & Smith, B.H., (2017) Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. The Cochrane Library.

Goldenberg, D.L., Schur, P. and Romain, P., (2013) Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of fibromyalgia in adults. UpToDate: Wolters Kluwer.

Macfarlane, G.J., Kronisch, C., Dean, L.E., Atzeni, F., Häuser, W., Fluß, E., Choy, E., Kosek, E., Amris, K., Branco, J. and Dincer, F., (2016). EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the rheumatic diseases.

Phillips, K. and Clauw, D.J., (2013) Central pain mechanisms in the rheumatic diseases: future directions. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 65(2), pp.291-302.

Wolfe, F., Clauw, D.J., Fitzcharles, M.A., Goldenberg, D.L., Katz, R.S., Mease, P., Russell, A.S., Russell, I.J., Winfield, J.B. and Yunus, M.B., 2010. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis care & research, 62(5), pp.600-610.