A few months ago a patient presented into the musculoskeletal outpatients clinic with lower limb arthralgia. When discussing her past medical history, she mentioned being diagnosed with Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS), adding, “I bet you have no idea what that is?” She was right, I didn’t.

Whilst this lack of knowledge of course wasn’t the be all and end all, I knew that at that moment I had missed one of the many early opportunities in an assessment to gain patient confidence. I later considered how our first meeting could have gone if I’d had an idea of her condition, its links to musculoskeletal practice and the potential burden of this on her life.

Researching Sjögren’s helped in our following treatment sessions and it is, perhaps, unsurprising that the first ever UK guidelines for managing adults with Sjögren’s were published only recently this year (Price et al., 2017).

What is Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS)?

SS gets its name from the Swedish Ophthalmologist, Henrik Samuel Sjögren (1899 – 1986). Briefly mentioned in my recent Voices column, http://www.physiospot.com/opinion/spotting-the-signs-extra-articular-manifestations-in-rheumatology/, SS is an autoimmune, rheumatic disorder outlined in the British Society for Rheumatology’s (BSR) long term conditions framework.

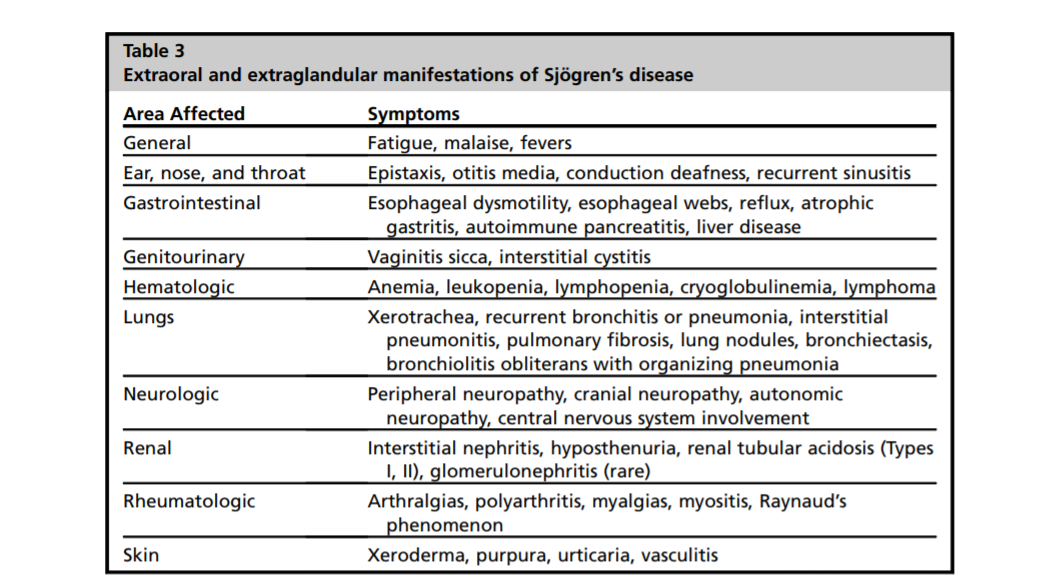

Sjögren’s (Sho-Gren’s) is a complex condition that is most commonly associated with oral and ocular dryness, fatigue and pain. It is known to predominantly affect the moisture producing glands of the body as well as having neurologic, respiratory and systemic components (Segal et al., 2008; Price et al., 2017). Chronic dry cough and dry mouth (xerostomia) are characteristic of SS and patients suffer with reduced salivary flow rate, increased saliva viscosity and dry mucous membranes (Price et al., 2017). Pulmonary manifestations include interstitial lung disease and pulmonary cysts.

Chronic dry cough and dry mouth (xerostomia) are characteristic of Sjögren’s Syndrome

Systemic features, seen in approximately 70% of patients, involve joints, lungs, skin and both peripheral and central nerves (Price et al., 2017), however, the neurological components have varying prevalence in SS. Alegria et al. (2016) found that peripheral and central neurological manifestations were about 15% and 5%, respectively. They felt that these manifestations were associated with greater disease activity and more common in patients with prior neurological involvement. The authors recommended that clinicians be more attentive to neurological signs in SS in general. Pure sensory and sensorimotor neuropathies were the most common peripheral nervous system manifestations in those with SS, whilst involvement of cranial nerve V (trigeminal) has been described also in Sjögren’s.

Furthermore, SS has been known to have links with both fibromyalgia and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Carsons et al., 2017; Price et al., 2017), an increased risk in developing lymphoma, and a higher prevalence among women (Segal et al., 2008).

There are more overlapping conditions too, most notably thyroid disease, primary biliary cirrhosis and coeliac disease (Price et al., 2017); once again the need to have an awareness of the wider links proves necessary in assessment and management.

As with several rheumatology conditions, there is often a delay between symptom onset and diagnosis in SS. Shiboski and colleagues (2017) developed an international set of diagnostic classification criteria for primary SS using guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), which are well worth further review for those interested.

Published Guidelines

There is currently no-known cure for SS, the treatment recommendations are therefore designed to manage symptoms, prevent further damage, improve quality of life and help clinicians select the appropriate treatment for patients.

Carsons et al. (2017) have published treatment guidance for rheumatologic manifestations in SS. The guidelines were based on a review of published studies, case reports and input from both physicians and patients. Unfortunately, they found a paucity of well-designed, controlled studies in the literature. They explored a number of immunosuppressant treatments as well as non-pharmacologic interventions in their review and, although pharmacological management is out of the remit of this article, it is interesting to know that some biologics, such as anti-TNF therapy, are not recommended in the treatment of SS.

Of relevance to physiotherapists was Carson et al.’s focus on fatigue. The causes of fatigue in SS are numerous and the only strongly recommended treatment of fatigue was exercise, which ‘provides the same benefit for SS patients that is seen in patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), SLE, or Multiple Sclerosis (MS)’.

More recently, the BSR published their UK guidelines in the management of SS (Price et al., 2017), including both non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments. Their guidelines are accredited by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Price and colleagues stress the importance of holistic management and emphasise non-pharmacological therapies and general support. Their easy-to-read document covers the management of ocular and oral manifestations as well as the systemic (extra-glandular), pulmonary and neurologic. Lifestyle management strategies may benefit SS patients if fatigue is significantly affecting their ability to perform daily activities. Though there appears to be no ‘gold standard’ way to accurately measure the multifactorial nature of fatigue (Ng & Bowman, 2010). Such strategies recommended by NICE guidance for fatigue include sleep and activity management, relaxation techniques, cognitive behavioural therapy and graded exercise therapy (Ng & Bowman, 2010; Price et al., 2017).

Exercise ‘strongly recommended’ in Sjögren’s

It is great to see that exercise is again strongly recommended in yet another rheumatology condition, but, unfortunately, the exercise recommendations are far from detailed and based on inconclusive, scarce evidence. Both Carsons et al. (2017) and Price et al. (2017) found that patients with SS would benefit from ‘moderate to high intensity exercise’, both guidelines citing the same author from some 10 years previous (Strömbeck et al., 2007) to support these recommendations. It certainly is a useful starting point however it does leave many unanswered questions surrounding exercise in SS.

Difficulty Quantifying Exercise & Defining Fatigue in SS

Strömbeck et al. (2007) investigated the effects of a 12 week exercise programme on women with primary SS. Their treatment group completed ‘high-intensity’ Nordic walking exercise for 45 minutes, 3x per week. The control group completed ‘low intensity range of motion exercises’ at their homes 3x per week for no specified length of time. The authors found reductions in fatigue and increases in aerobic capacity following the 12 week exercise programme and thus concluded that aerobic exercise of high intensity can be beneficial to patients with SS. The small sample size in the study cannot be ignored as a limitation; there was significant attrition of the recruited participants (94 to 19).

Fatigue is common in many rheumatology conditions and often has a huge impact on patients’. Segal et al. (2008) focused their research on the impact that fatigue has on quality of life in SS. They used a number of various fatigue measures. The main purpose of this study was to investigate the relative contributions of disease status, behavioural and immunological factors to fatigue in SS. Their main finding was that psychological factors are determinants of fatigue and that depression correlated with fatigue severity, despite not being causative of fatigue.

Summary

Sjögren’s Syndrome (SS) is a complex, autoimmune, rheumatic disorder that may be treated by many different healthcare professionals. As with too many rheumatology conditions, there can be considerable delay to diagnosis, thus awareness of these conditions must become commonplace. Signs of oral and ocular dryness are no longer the only salient features in Sjögren’s; the disease encompasses respiratory, neurologic and systemic components too. Fatigue is prevalent in SS but presents itself in a multifactorial nature that is not yet fully understood or defined.

Moderate to high intensity aerobic exercise is strongly recommended for treatment of fatigue in patients with SS, however, there is a paucity of evidence surrounding exercise recommendations and more robust research is needed to ascertain exercise specifics including type, duration and frequency.

With two comprehensive guidance documents published this year, it seems apt to discuss this condition now. Raising awareness of Sjögren’s, and of rheumatology as a whole, helps empower patients, their families and multidisciplinary clinicians. It might well be you that gets asked today, ‘Have you heard of Sjögren’s?’

Chris

#ThinkInflammatory

References

Alegria, G.C., Guellec, D., Mariette, X., Gottenberg, J.E., Dernis, E., Dubost, J.J., Trouvin, A.P., Hachulla, E., Larroche, C., Le Guern, V. and Cornec, D., (2016). Epidemiology of neurological manifestations in Sjögren9s syndrome: data from the French ASSESS Cohort. RMD open, 2(1).

Carsons, S. E., Vivino, F. B., Parke, A., Carteron, N., Sankar, V., Brasington, R., Brennan, M. T., Ehlers, W., Fox, R., Scofield, H., Hammitt, K. M., Birnbaum, J., Kassan, S. and Mandel, S. (2017) Treatment Guidelines for Rheumatologic Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome: Use of Biologic Agents, Management of Fatigue, and Inflammatory Musculoskeletal Pain. Journal of Arthritis Care Research, 69, pp.517–527.

Ng, W & Bowman, S. (2010) Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: too dry and too tired, Journal of Rheumatology,49(5), pp.844–853.

Price, E.J., Rauz, S., Tappuni, A.R., Sutcliffe, N., Hackett, K.L., Barone, F., Granata, G., Ng, W.F., Fisher, B.A., Bombardieri, M. & Astorri, E. (2017). The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of adults with primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Journal of Rheumatology, pp.166.

Segal, B., Thomas, W., Rogers, T., Leon, J. M., Hughes, P., Patel, D., … Moser, K. (2008) Prevalence, Severity and Predictors of Fatigue in Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome. Journal of Arthritis and Rheumatism, 59(12), pp.1780–1787.

Shiboski, C. H., Shiboski, S. C., Seror, R., Criswell, L. A., Labetoulle, M., Lietman, T. M., Rasmussen, A., Scofield, H., Vitali, C., Bowman, S. J., Mariette, X. (2017) 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Journal of Arthritis & Rheumatology, 69: pp.35–45.

Strömbeck, E., Theander, &, L., Jacobsson (2007) Effects of exercise on aerobic capacity and fatigue in women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome, Journal of Rheumatology, 46(5), pp.868–871.