The focus of the fourth week of the Emerging trends in global health course has been governance for global health, health system financing and the human resources issues related to health care workers education and migration.

Governance for global health

Since is establishment in 1948 the World Health Organisation (WHO) has been one of the primary actors in driving the health agenda globally and remains the only body able to create legally binding treaties (there are currently two; the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and International Health Regulations (IHR)). Overtime the number of other organisations involved in this field has grown dramatically such as national government departments, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) e.g. the NCD Alliance, and private organisations and foundations e.g. the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Many of these organisations have overlapping areas of activity and conflicting interests. One of the most important issues facing global governance is to ensure the available funding and efforts are aligned with global health needs and priorities.

Universal health coverage

Universal coverage (UC), or universal health coverage (UHC), is defined as ensuring that all people can use the promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative health services they need, of sufficient quality to be effective, while also ensuring that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.

World Health Organisation

The provision of universal health coverage to all global citizens has been an aspiration of WHO since its inception and continues to be promoted in its more recent work. See WHO 2010 report The world health report – Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Unfortunately there is considerable progress to be made towards achieving this goal. Preker et al (2004) estimates that “a high proportion of the world’s 1.3 billion poor have no access to health services simply because they cannot afford to pay at the time they need them.” The impact extends beyond this according to a WHO News release (2005) that estimates that “each year 100 million people slide into poverty as a result of medical care payments. Another 150 million people are forced to spend nearly half their incomes on medical expenses.”

Systems of universal health coverage involve three key functions:

- Revenue collection – voluntary or compulsory health insurance, taxation and fees at point of purchase.

- Risk pooling – spread the financial risk associated with the need to use health services through collective prepayment.

- Strategic purchasing – national, organisational and personal purchasing of health services.

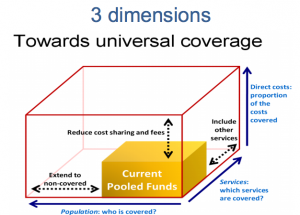

The key questions to be considered in the development of a universal coverage system are:

- Who is covered?

- Which services should be covered?

- How much of the costs should be covered?

Healthcare workers: appropriate skills and the brain drain

The Lancet Commission “Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world” in 2010 identified that the current systems of educating healthcare professionals are in need of significant review due to the changing nature of the global health challenges (such as the dramatic increase in non-communicable diseases) and the failure of current approaches to distribute the benefits of healthcare equitably.

‘four recent reports concur that health professionals in the USA, the UK, and Canada are not being adequately prepared in undergraduate, postgraduate, or continuing education to address challenges introduced by ageing, changing patient populations, cultural diversity, chronic diseases, care-seeking behaviour, and heightened public expectations.’

Frenk et al. (2011, p.1)

They suggest educational reforms such as the utilisation of competency driven approaches, inter-professional and trans-professional education to reduce professional silos, utilising e-learning technologies and strengthening educational resources (Frenk et al., 2010).

Globally, there is a shortage of healthcare workers and a serious issue facing developing countries is the ‘brain drain,’ caused by the migration of health workers to higher income countries (Serour 2005). This has serious implications for these countries efforts to provide healthcare for their own citizens. This situation has led to a voluntary WHO global code of practice (WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel 2010) which has yet to be widely adopted (MedicusMundi 2013).

Implications for physiotherapy/ physical therapy

While many of these issues are not of direct relevance to a practising physical therapist, it may be interesting to be aware of the complex and fragmented nature of the organisations and interests that participate in setting the global health agenda, especially when we consider supporting these organisations through fund raising etc.

There are many differences in the make up and operation of the healthcare systems within which we work. It is important to acknowledge the implications of universal healthcare coverage and how this is widely accepted as a model to aspire to. However the nature of the implementation of any universal healthcare coverage systems and in particular when and how the users of that system pay for its services will have significant implications for equity of access and user behaviour in utilising that system. For example a system such as the UK’s NHS which is entirely funded by taxed prepayment and is free at the point of delivery will offer a high level of equity of access but will incur levels of inappropriate use by some users. Alternatively any system which requires some level of payment at the point of delivery will reduce levels of mis-use but will reduce equity of access by the poorest in society.

The Lancet commission has raised serious questions for current education programmes for healthcare and so we need to ensure that we are appropriately skilled for the most important health issues facing our patient population including non-communicable and chronic conditions. We also need to be aware that we practice as part of a multidisciplinary team and so we should strive to improve the effectiveness of that team as a whole for the benefit of our patients. If we are involved in education ourselves then we should take the time to read and reflect on this commission’s findings to consider if our own programmes and courses need to be changed.

If we are involved in recruitment we should consider the WHO code of practice for the recruitment of overseas health personnel and consider how this should impact on our organisations recruitment policies.

Implications for Physiopedia

It is important for Physiopedia to recognise it has a role (albeit a small one) within the global health agenda and so it should aim to develop educational resources and articles in line with global health priorities as well as those that reflect the specific needs of the profession.

The Lancet commission on healthcare education suggests that open on-line resources such as Physiopedia can have an important role to play in addressing the issues they identified. One such issue is working to break down the professional silos occupied by each profession and to promote the multidisciplinary nature of healthcare. To achieve this Physiopedia needs to look to incorporate the multidisciplinary aspects of healthcare in more articles, case studies and educational programmes through adding the perspectives and contributions of other disciplines where appropriate.