by Clare Farrance

After graduating from Nottingham University in 1999, I started off my professional career in Scarborough General Hospital where I had a great time and got all basic, foundational skills we need in physiotherapy. But I quickly realized I wasn’t quite cut out for the regular working life in England.

I went ahead and got some training in cross cultural work and primary healthcare to give me a broader foundation. Through all this I had some amazing opportunities and ended up teaching basic physiotherapy principles to doctors working in government hospitals and clinics in the north of Afghanistan, training women in mother and child health in Myanmar, testing peoples eyesight in East Timor and providing them with glasses as needed, primary health care in South Africa and teaching hygiene and treatment of common health problems in the garbage cities in Cairo. I really enjoyed the variety of places I got to see and how it challenged me to think outside the box and improvise. I was very often out of my depth yet had to get stuck in and figure it out anyway. For example what do you do when you don’t have theraband but want to strengthen someone’s shoulder muscles…answer, use a bike inner tube!

After a whole host of short-term work I became itchy to get stuck in somewhere that I could leave more of a mark and learn the language and culture beyond the basics you pick up in a few weeks. For the longest time I was afraid of going to a Muslim country but after being in Afghanistan and realizing that they are just regular people who want to get on with their lives I felt more confident to give it a go. So here I am, now 3 years on in Iraq. I figured this was one of the many places in the world where I would never be in short supply of physiotherapy work and I sure haven’t been disappointed. There is enough work here to last a lifetime!

The history of physiotherapy is Iraq is complex. It has been practiced for the last 30 years or so since the Baghdad Institute of Technology began a 2-year diploma course. This has since transitioned to a degree programme but remains highly theoretical. On the whole physiotherapists work more like technicians carrying out doctors instructions. There is little in the way of assessment, note keeping, clinical reasoning or holistic thinking.

The Kurdish uprising in the north of Iraq in 1991 led to an unstable political and economic situation and consequent collapse in the primary healthcare system. This created an enormous gap between the health care needs of the population and the regional healthcare services. This year also led to this area becoming a no fly zone protected by US and became known as the Kurdish autonomous region. This opened the way for a flood of non-governmental organisations (NGO) to come into country to begin to meet some of the more basic health care needs. At this time many people had fled to the mountains and were living in refugee camps unsure of if it was safe to return to their cities.

Up until the late 1990s there was no physiotherapy training in the north. This meant there was a significant percentage of the population without ANY trained physiotherapists. The implications for this particularly at this time were huge since there were a large number of people who were victims of land mines, torture and generally poor medical services etc.

Many years on there are still lots of challenges to be faced. How do you raise the standards in a country where the need isn’t greatly seen by the government, where there is no title protection (anyone can stay there are a physiotherapist), there are no standards of practice, poor training with no concept of continuous professional development, no notes are kept, very little in the way of patient assessment take place, little organisational structure, no consequences for poor practice, doctors don’t understand your role, the general public has a poor view of you, you’re not paid well, you have very low grades to be accepted.

Given all the above, where do you start? For better or for worse I began by getting the head physiotherapists together and asking them what their greatest felt needs were. They came back with saying they wanted regular training, a degree course, an improved working relationship with the doctors and improved pay (no surprises there!), and a physiotherapy association. I looked at the list and the skills I had (since I was working on this alone at the time) and figured putting together a system of regular in-service training (IST) was something I could manage. So I spent that year setting up and running IST in 5 different centres over the city. Three of centres dropped off quickly, pretty much as soon as they realised that they would have to participate in preparing teaching! One centre responded really well and carried on with the training completely independently. The other centre persevered with A LOT of encouragement from myself. It was tough going!

I saw that the staff had really low morale and little motivation to improve but I really wanted to encourage a move towards professionalism and for them to understand their role and take responsibility in this. So that was when I decided to organise the first ever physiotherapy conference in the region and probably country.

This was a great success. More than 200 delegates attended the 3-day conference. An Australian Physiotherapist with over 25 years experience in clinical work was the lead speaker. Through the lead lectures she shared about the need to develop the profession of physiotherapy in Kurdistan, clinical supervision and the role of continuing professional development and the need for clinical reasoning and evidence based practice. These lectures reinforced what I had already been trying to attain and encourage through the in-service training programme.

I also wanted to provide an opportunity for the therapists to have some input into their clinical practice so 2 of the days had elective seminars. These looked at several case studies from clinical practice, neurological rehabilitation, exercise in the elderly and how to promote physical activity in the community, music therapy using drum circles in paediatrics, how to manage a physiotherapy team and recent research into the role of physiotherapy on patients with osteoarthritis of the knee joint. A mix of national and international staff taught seminars.

The final day of the conference provided a chance for doctors to attend. This was a great opportunity for the physiotherapists to discuss alongside the doctors how we can be improving physiotherapy in the Kurdish Regional Government.

The following year a Dutch colleague joined me. This was great since two are always more effective than one! We started off the year by forming a local team in Sulaimany, which we called Moving Physiotherapy Forward (MPF). This is a group of highly motivated doctors and physiotherapists with which we meet and discuss and plan and implement the development in the governorate. In the future we would like to have teams like this in each of the 18 governorates in Iraq as well as having a regional and national team. The aim of these teams is to share in the work and carry the responsibility for their governorate.

I’m keen to see physiotherapy standards improve across the whole of Iraq. Unfortunately, at this stage, due to security and in-country politics and challenges between the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) and Central Government (CG) it has been deemed wiser to focus on working regionally.

So what next…well our to do list for physiotherapy in Iraqi Kurdistan and Iraq includes:

- Setting up an Iraqi physiotherapy association;

- Starting a BSc degree to international standards in the north;

- Upgrading the skills of the local physiotherapists;

- Facilitating other internationals coming in to help with training;

- Facilitating MPF teams in each governorate;

- Establishing a department/ unit of physiotherapy within the government who will be responsible for development;

- Facilitating a regional development team;

- Figuring out some funding to make all the above happen. It is becoming more and more difficult for us as an NGO to acquire funding for projects in Iraq since outside funders seem to look at Iraq and say it is so rich in oil and so are reluctant to give. This is true, but this money does not always reach the basic needs of the people. One of those needs is clearly in the areas of health care, physiotherapy and disabilities. Hence little funding comes our way right now.

In the long run, without this issue of quality physiotherapy services being addressed, patients will continue to suffer from disabilities and pain due to chronic, poorly managed conditions. However, this problem is solvable if physiotherapy is seen as a priority and an organised, coherent structure is set in place across the region and nation meeting world standards.

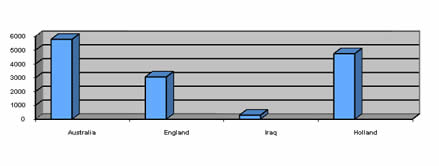

For those of you who like to see the statistics here is a graph representing the number of physiotherapists per population head of 5 million:[1] It’s pretty easy to see the need for an increase in numbers of physiotherapy staff, especially in this war torn country.

It’s pretty easy to see the need for an increase in numbers of physiotherapy staff, especially in this war torn country.

And so we persevere hoping that as we try and pull together the national physiotherapists and doctors they will work together in moving physiotherapy forward one step at a time.

[1] Road to Recovery, E Hoogeland, 2004