Clinical prediction rules are tools that intend to guide clinicians in their everyday clinical decision making. They provide physiotherapists with an evidence-based tool to assist in patient management when determining a particular diagnosis or prognosis, or when predicting a response to a particular intervention. They are most commonly used in musculoskeletal practice but can be found in other areas such as respiratory settings. They tend to be prescriptive in nature and the popularity has been increasing in recent years but are they actually logically and factually sound?

According to Beattie and Nelson (2006) a clinical prediction rule is “is a combination of clinical findings that have statistically demonstrated meaningful predictability in determining a selected condition or prognosis of a patient who has been provided with a specific treatment“. Steyerberg et al (2013) state that a CPR is a statistical combination of multiple predictors from which risks of a specific endpoint can be calculated for individual patients. Basically it is the process of choosing a treatment based on the evidence that for other people with a same/similar presentation the treatment worked.

CPRs are more complex than diagnostic or prognostic rules as they predict differences in outcomes under different conditions, and their development requires experimental studies to examine effectiveness followed by validation of the tool itself. A 2013 study called PROGnosis RESearch Strategy raised concerns about the rate of CPR publication without thorough validation through experimental studies.

The PROGRES study was published soon after a 2010 systematic review by Stanton et al found that 13 commonly used CPRs were unvalidated and therefore they concluded that there was little evidence to support the use of CPRs for many musculoskeletal practices. This has also been found to be true for CPRs used for back pain, spinal manipulation and many rehabilitation practices throughout the middle of the last decade. In essence there has been too much focus on the creation of new CPRs rather than validating, updating and refining the existing ones.

A new systematic review published in the Journal of Clinical Epidimiology has aimed to build on the work by Stanton et al by reviewing CPRs that have undergone validation testing for predicting response to physiotherapy-related interventions for outpatient musculoskeletal conditions, and to critically appraise associated derivation studies.

Discover Treatment Based Classification for LBP

Methods

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines and a search strategy and fowchart are availaible within the article. The Steyerberg definition of CPR was used. Studies which aimed to validate a published CPR that stratified patients with musculoskeletal conditions to different interventions relevant to outpatient physiotherapy practice were included. Only studies with a comparison or control arm were included. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria is available.

Pubmed, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane Library were the databases used for the review. The search was imited from 2007 – Sept 2020 and the justification for this was to build on Stanton et al’s work.

Two review authors screened the search results and excluded irrelevant studies. To review the remaining articles the two review authors were joined by a third. Disagreement about inclusion or exclusion were resolved by consensus.

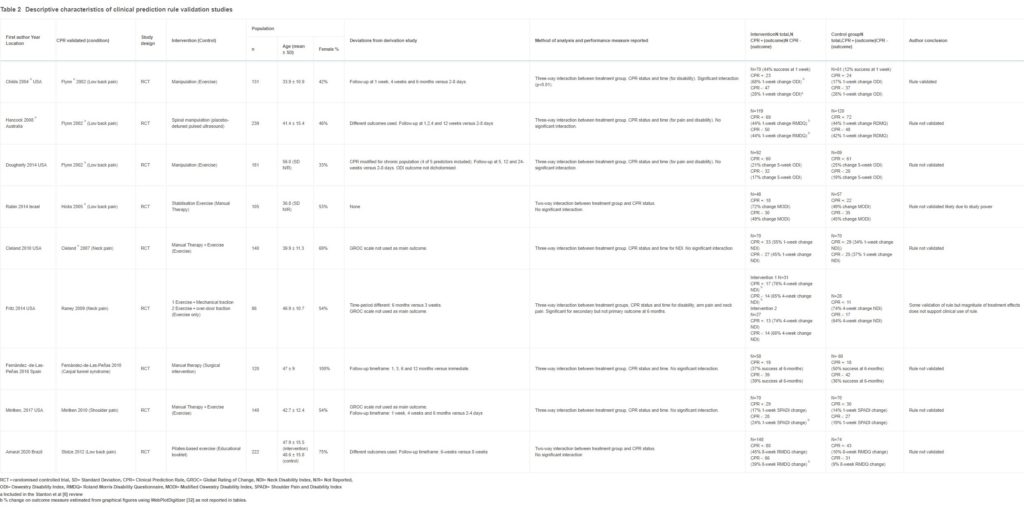

In total 9 articles were included within the review (reduced from 6,058 studies) and CPR features, original derivation study reference, study design, setting, population, musculoskeletal condition, proposed treatment, definition of successful outcome, follow-up duration, sample size and demographics were all extracted.

Risk of bias was a big focus for the authors therefore a two step process was used to ascertain the level of bias of included studies. This was done by using the PROBAST tool and then the Cochran risk of bias tool.

Results & Clinical Importance

Included within the review are seven derivation studies of which 6 were developed in the USA and one in Spain. Of these three were for low back pain, two for neck pain, one for carpal tunnel syndrome and one for shoulder pain. Treatment options within these CPRs included manipulation, traction, exercise or a combination of these treatment. Duration of follow-up ranged from immediate to 8 weeks.

A controlled design was not used in any derivation study despite aiming to develop predictive rules. All had sample sizes of 54-95 participants. The ratio of number of patients with positive outcomes to the number of variables in multivariable analysis ranged from 2 to 5, when PROBAST recommends inclusion of at least 20 for valid analysis.

Nine validation studies are included within the review. Of the CPRs included within the one CPR, for predicting response to spinal manipulation for LBP, underwent validation testing through three different studies. Each of the remaining CPRs underwent a single validation study. Six validation studies had longer follow-up times than the original and six used different primary outcome definitions than the original derivation studies.

Based on the findings of this systematic review, and due to it’s quality and rigour, it is difficult to endorse the use of clinical prediction tools within musculoskeletal practice. If using CPRs it is important to assess the validation of the tool first.

All of the validation studies were RCTs and were overall of good quality however it was unclear if many were blinded and several validation studies reported different outcome definitions than derivation studies and the rationale for this was not fully explained.

When looking at the statistics it appears that all of the rules were designed for identifying patients who were most likely to respond to treatment rather than ruling out those who would not respond. Of the validation studies only one recommended the use of a CPR. This was the CPR derived by Flynn et al for back pain and spinal manipulations for short term pain improvement. However two subsequent validation studies were unable to replicate the findings. All of the other CPRs did not reach statistical significance and therefore remain invalidated.

Based on this systematic review it is difficult to endorse the use of clinical prediction tools within musculoskeletal practice, if using CPRs it is important to assess the validation of the tool first. An explanation of which tools work best for back pain, and to explore more of the concepts explained within this article take part in the course listed below.