Hydrotherapy is a great treatment choice for people living with OA knee but what does exercise in the water look like? In this post we will explore the evidence base.

Knee osteoarthritis is characterized by the irreversible loss of articular cartilage from the condyles of the femur and plateau of the tibia. As the damage progresses pain increases resulting in a reduction in quality of life.

As the symptoms progress people with OA generally reduce their physical activity due to pain. Unfortunately, activity avoidance results in accelerated progression of the symptoms and loss of functional whereas partaking in the right type of exercise actually improves and prevents symptoms.

Almost all of the guidelines list land-based exercise as a corner stone for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. However for some people pain can prevent engaging with a treatment programme and a different approach is required.

This is where hydrotherapy comes into its own as it offers offloaded exercise in a warm therapeutic environment. It has also long been used and shown to be effective in the management of knee OA partly due to its perceived pain reducing effect during and immediately after exercise.

But what does a hydrotherapy exercise programme look like when treating knee OA?

Aquatic Exercise for Knee OA – The Evidence

In a both a systematic review by Waller et al and Cochrane Review by Bartels et al it was demonstrated that hydrotherapy significantly improves pain in knee OA. However measures of physical function demonstrated only a very small or no improvement, so what’s going on?

Well, the main explanation is that there was a lot of variety in intensity of exercise chosen and primary outcomes. All different types of exercise were thrown into exercise plans making it hard to draw firm conclusions.

So we have to turn to RCTs and other trial designs to find out which exercises we should use.

How to Transition from Land to Aquatic Exercise for Knee OA

As with land based exercise the treatment plan should be individualised to the patients needs and a great way of approaching this is by using the ICF. To be most effective the programme should focus on one main outcome and be performed twice a week for between three and six months.

If you need ideas, images or videos of hydrotherapy exercises to send to your patients then take a look at a Physioplus PRO account which included a telehealth platform. As a starter though let’s break things down into 4 different groups of exercise:

- Flexibility and ROM

- Aquatic Resistance Training

- Cardiovascular

- Neuromuscular and Balance

Flexibility and Joint ROM

Static stretching in warm water is easier than land. A great tip here is to use the buoyancy of water with floats to aid the stretch and allow the patient to “relax” into the stretch.

Furthermore it appears that muscle spindle activation decreases during passive immersion this in combination with decreased pain allows more effective passive soft-tissue stretching.

Sticking to the cellular biology – the active movements in warm water also increases cell activity in the fascia further improving mobility of soft tissues and joints and this largely explains the short term pain and mobility increases reported in the evidence.

Aquatic Resistance Training

The prescription of resistance training should always be based on the 1 rep max. Low intensity strength training involves 10-15 repetitions at 40% of 1RM, moderate is 6-10 repetitions at 40-60% of 1 RM and high is 6-8 repetitions >60% of 1RM. But is this the same in the water?

It’s a bit difficult to exactly measure muscle activity the same way as on land as water dynamics and gravity don’t work equally on the muscles. Therefore one rep of an exercise between two people exerts a different force.

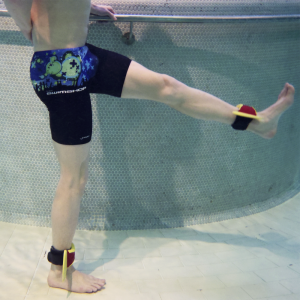

One method for controlling resistance during aquatic resistance training is the use of equipment that increases the surface area of the limb. The most common example is a resistance boot which can increase resistance by upwards of three times during under water movement.

Generally speaking programmes including 5-6 lower limb aquatic resistance exercises focusing on the knees and hips have been shown to be most effective. Aim for each exercise to be completed over 30-60 seconds with each repetition being as hard and fast as possible.

Each leg should be consecutively exercised without rest followed by 30-45 seconds of rest with 2-4 sets per exercise, with 1 minute rest between each exercise. Overall the main part of the session should last approximately 30-40 with a 10-15 minutes warm up and cool down rounding out an hour.

Cardiovascular Fitness

Rating of perceived exertion (RPE), percentage of V02max or heart rate maximum are great tools to use to evaluate cardiovascular improvement pre-post hydrotherapy.

Deep water running, calisthenics, high repetition aquatic resistance exercises and swimming are all examples of aerobic training in water. Most improvements are seen when exercises are performed 3-5 times a week for 30-60 minutes and follow recommended guidelines: moderate intensity is described as RPE 5-6/10 (40-60% of V02 max/HR max) and 7-8/10 (60-80% of V02 max/HR max) for vigorous.

Neuromuscular and Balance Exercise

Land-based neuromuscular training is a great way of improving function and pain in people living with knee OA. But can this be replicated in the water?

A programme developed by Hinman et al integrates many common aspects of land-based neuromuscular training, while using the body weight supporting effect of buoyancy to assist the movement and make this type of training accessbile to those with high levels of pain and to good effect too.

The programme used double and single leg squats, steps up, lunges and calf raises, just in the same way you would on land. A top tip is to gradually decrease the water depth to increase weight-bearing aspects of the exercise which not only makes it more difficult but is an excellent way to transition to land based exercises.

This post was originally published November, 2016 and written by Ben Waller. The page has now been updated for freshness, accuracy and comprehensiveness.