Hello to all and welcome to my blog courtesy of stopsbackpain.com.au. Today we’re going to talk about clinical excellence.

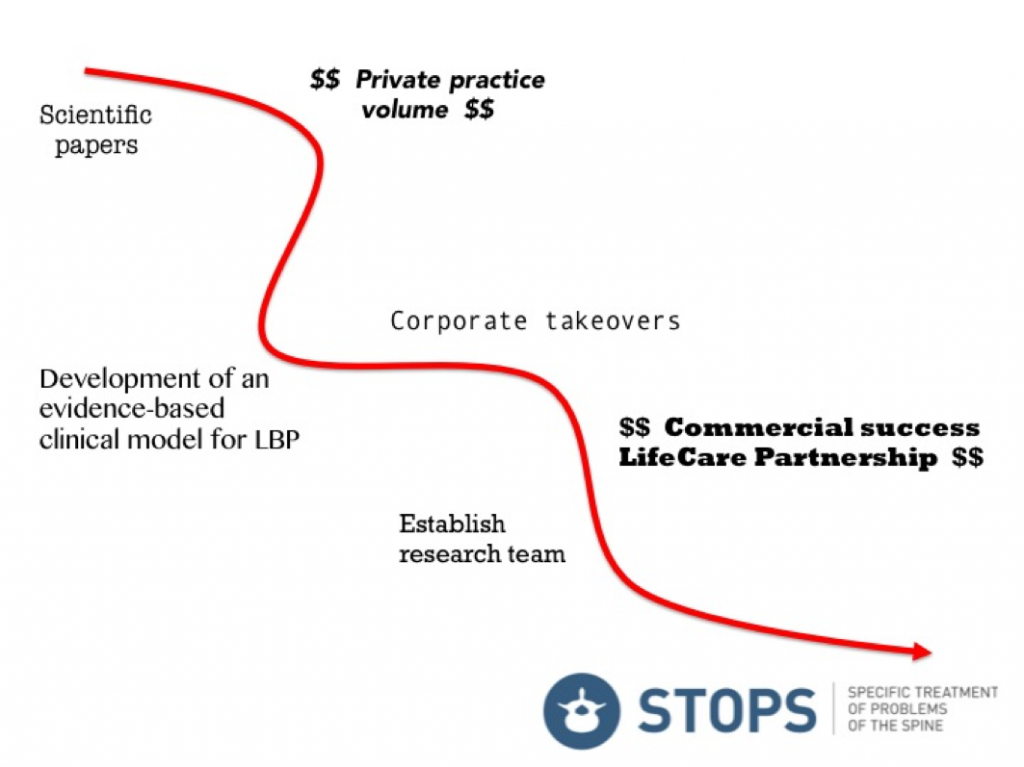

On graduation from physiotherapy in 1988, like most practitioners, I had a goal of maximising clinical excellence when treating patients. However I certainly didn’t envisage the path that unfolded as summarised in the figure below. By reading the scientific literature, developing a clinical model and various commercial successes, I eventually ended up completing the STOPS Trial; the pinnacle of my career so far.

Over this journey I have mentored hundreds of practitioners from the clinical and commercial perspective. Those who have stayed with me have forged their own path of clinical excellence framed within an evidence-based model. Most of these practitioners are also highly successful commercially.

There is a high rate of attrition in the allied health and physiotherapy professions. In my own experience, clinical excellence leads to a long and satisfying career in allied health which can overcome this issue. So what are the three steps to clinical excellence?

Step 1 – Apply evidence-based practice

There is so much information available for practitioners on the management of musculoskeletal pain. Can practitioners realistically be across all these management approaches for every region of the body as part of an aim to be clinically excellent?

I don’t believe so.

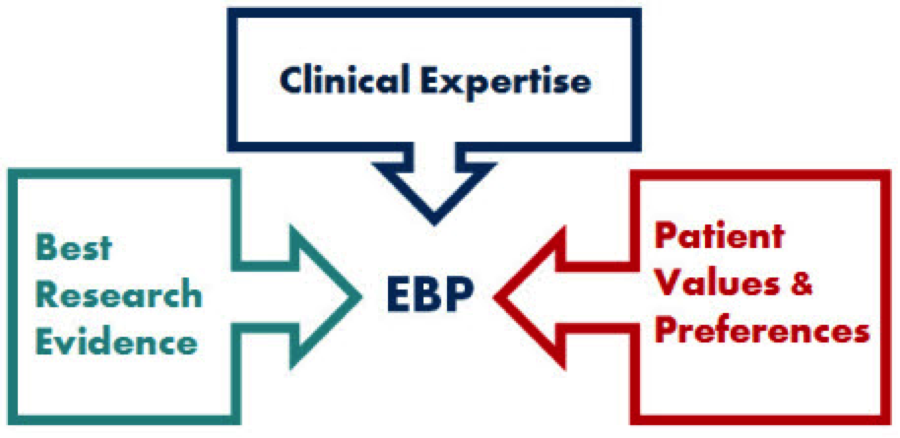

In my own clinical practice, clinical excellence is defined by the principles of evidence-based practice (see figure below) with a healthy emphasis on the “clinical expertise” and “patient values & preferences”. Of course such an approach carefully evaluates the best research evidence.

I’ve written a free eLearning module on the application of evidence-based practice to improve clinical excellence. Check it out here.

Step 2 – Find an experienced clinical mentor

I was lucky enough to have two fantastic mentors in my early physiotherapy career. Lyn Watson was the first person to demonstrate to me in the cubicle what clinical excellence was. There’s nothing like seeing an expert practitioner work their magic with a real patient.

Michael Kenihan was the person who identified my clinical skills in back pain and encouraged me to develop a network of like-minded evidence-based practitioners.

If you want a mentor I encourage you to:

- Develop a special interest and find an expert in that field

- Do your research on them and then make contact asking to observe

- If you are successful, during observation be respectful and ask questions

- Say thank you and request whether you can repeat the experience

If you are lucky this person will take you under their wing and develop your clinical excellence.

Step 3 – Select your sources carefully

In this age of instant communication, misinformation is everywhere. This is perfectly illustrated in the climate change debate where critics of the science on global warming use strategies such as:

- Overstating level of scientific disagreement

- Highly selective citation of research data

- Using slogans to over simplify complex issues

- Manipulation of (social) media

- Publication in media with specific agenda

Paul Hodges describes a common misconception that a motor control approach is uni-dimensional (specific muscle activation) and a single solution for the management of LBP (Hodges 2013). Despite this, numerous highly esteemed researchers make misleading statements regarding motor control exercises such as:

“We should probably avoid suggesting that ‘‘core stability’’ exercises provide the absolutely specific treatment that will resolve back pain and improve function.” (Cook 2008)

“This ‘belief system’, which I once advocated… (focuses on) enhancing spinal stability… instructs patients to contract their ‘stabilising’ muscles prior to spinal loading and during movement. This reductionist approach to dealing with complex disorders in a simplistic manner clearly hasn’t delivered.” (O’Sullivan 2012)

“Maybe those who had practice foundations based on motor control philosophies can admit they were not quite right… (Research) resources need urgent diversion elsewhere… Maybe the main drivers of this approach could even apologise for hogging the conferences, agenda and research dollars?” (Butler 2014)

This is one example among many where over reaching statements can create confusion amongst practitioners and patients (for the record, a comprehensive and balanced exploration of consensus/divergent views on motor control has recently been published) (Hodges 2013).

Sources of information for practitioners should provide balanced evaluation from an evidence-based perspective and not be obviously pushing a narrow opinion. Musculoskeletal pain is a complex phenomenon and no one treatment can provide an easy solution.

The wash up…

Clinical excellence should be the aim of every dedicated practitioner involved in musculoskeletal pain. Follow these three steps and you’ll be on your way!

If you’re interested in a free eLearning module on this and other topical issues click here, subscribe and follow the links.

I’d love to have a dialogue with the Physiopedia audience so feel free to comment below.

Until next time

Jon

References

Hodges, P. (2013). Spinal control: the rehabilitation of back pain. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingston. (currently a 20% discount for Physiopedia users!!)

Cook, J. (2008). “Jumping on bandwagons: taking the right clinical message from research.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 42(863).

O’Sullivan, P. (2012). “It’s time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 46(4): 224-227.

Butler, D. (2014). Motor control to motor freedom NOI.